On Road | KUKJE GALLERY

On Road | KUKJE GALLERY

Feb 27, 2001 - Mar 24, 2001

K1

Seoul

INTRODUCTION

The frame, the four borders that delimit and edit the photographed object through the camera lens, the apparatus of inclusion and exclusion, has been most important in reviewing jungjin lee's photography. The well edited "framed" photograph, or the casual happening of a snapshot, all involves the camera frame as the primary mechanism that produces the meaning, the semantic sign of the photographed image. In her vigorous output during the past decade, Jungjin Lee has continuously worked with different notions of the camera frame. And in seems again of primary importance to discuss the ways in which the artist has been framing the photographed object in understanding her most recent work, the On Road series.

Jungjin Lee writes about her last series of American Desert photographs in 1997 that she attempted to resign the photographer's control of the frame as she concluded her representations of rhe desert landscape, And thereby the artist intended the natural presence of the landscape to come across in her photographs and the object to present itself, without the interjection of the artist's control or intentionality. It was an attempt to conclude the desert series by giving up the photographer's privilege over the photographed object. Therefore she chose methods of placing herself as part of the photographed object, part of the landscape, and mot in front of the camera. The result was a more vivid and untamed representation of the desert,what I sense was in a way an homage to the vast desert land which she had visited for years.

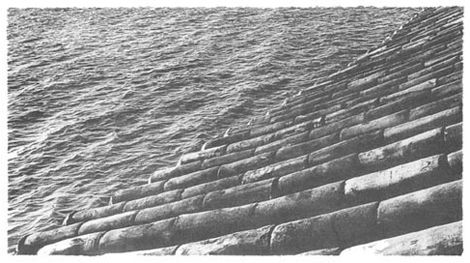

In her following sequel titled the Ocean Series, the type of landscape and the visual effect of jungjin Lee's photography had changed to a great extent. The choice of ocean as a subject matter was obviously significant. In the images of different textures of water ripples, water and sand surfaces, Jungjin Lee has framed an indistinct detail, or portion, of a landscape that is too vast to be captured by any framing device. And therefore the result is also a photography that visually works as abstract painting. In the choice of ocean, rather than seaside landscape, in the renditions of the general properties of water (and sand), and the framing of ocean as water, Jungjin Lee's ocean pictures deny the documentary function of photography. It is the most abstract and painterly work of the artist. The photographed object appears abstract and surreal in front of the camera, and the framing has simply recognized and captured such inherent properties of the object. The artist's involvement in the Ocean series has been to frame the natural properties of the landscape and it is the function of framing in which photography and painting are most different, although the visual image produced might be similar in effect.

The most recent On Road series is starkly different from her earlier works but it also shares some affinities with Jungjin Lee' s previous output. It is in some ways a continuum of her American Desert series from the early 90s in that On Road is also the result of her travels. As in her representations of the desert landscape, Jungjin Lee does not opt for vast vistas or scenic nature, but her interest remains on chance encounters with odd pieces of visual detail, with ambiguous formations in natural or manmade environment.

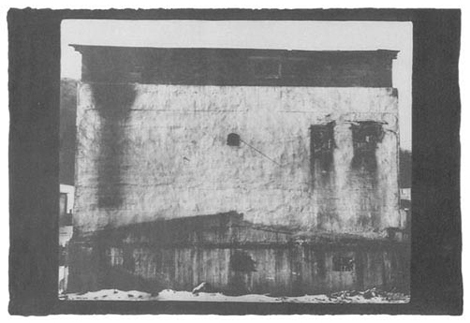

Jungjin Lee has produced quite a wide range of different images from around the countryside in remote areas in Korea, and others from abroad-scenes of empty barren fields, or haunting building facades, an abandoned street corner in a deserted old village, a serene fishing village, beautiful still shots of trees and houses. Most of her landscapes are distinctly Korean, where the horizon line, architecture, and types of trees are specifically local. The object, the scene that captivated the artist has been freeze-framed. Everything is very still: there is no suggestion of life or movement, but a complete silence lulls over the scenes where time stands still.

The unique aspect of the On Road series is the special format of the photographs. All the photos are bordered by a jet black thick border which forms a conceptually and visually important element in viewing the photographs. The borders complete the image, edit the image as a pictorial unit. Visually it immediately reminds one of viewing a blown-up strip of film wherein all stills are framed by a continuous black border. The border is a compositional element as well as a semantic sign-it renders the photographic image into a freeze-frame film still, that is a cinematic moment. It thus becomes a frozen moment from time and place, but the temporal and spatial aspect of the On Road photographs is ambiguous. The time is non specific, of rather there is an antiquated look to the images, suggestive of a distant past. The On Road photos are therefore not documents of a journey, but an aesthetic moment. It is a scene of poetry rather than analysis, a "rarefied cameo." And in accord to such representations, the artist has chosen to reemphasize the framing device of her photographs. Whereas she renounced the editorial function of framing in her late American Desert or Ocean series, the framing is made manifest in On Road. These are beautifully composed pictures, and photographed and presented as autonomous monents from her journey, as complete painterly pictures.

In many ways Jungjin Lee's photography is close to painting. Technically her prints are not mechanically reproduced multiples. The artist brushes a coating of light sensitive emulsion on handmade rice paper which produces brush marks on the imprint. These irregular brush marks capture the photographic image, and thus the layer of brush marks is visible through the photograph.This produces a painterly quality which is further enhanced by the use of Hanji paper which absorbs crisp details and strong contrasts of lights and darks.

The natural off white color and mat absorbent surface texture of the printing paper produce a soft and blurred image. Not unlike the Pictorialist photographer's work from the late 19th century, Jungjin Lee's work is also suggestive of the intentions of the early practitioners of photography who opted for such technique and material to elevate the status of photograph as the aesthetic image on a par with painting. But in dong so, Jungjin Lee's prints appear completely unique within current practices among photographers.

It seems that the status of photography as art has become even more problematic than it was during its infancy in the latter half of the 19th century. If anything or everything in terms of the visual image around us in daily life is photographic, then what are the viable conditions that are applied to evaluate good photography, or photography with artistic merit? Besides, with the load of photography discourse in circulation the informed viewer may be burdened by readings about what Barthes defined as denotation and connotation in the photographic image so that what is photographed is not an innocent documentatiopn, rather it is actually a myth and therefore not really what it looks like, but represents something that is culturally, politically and historically contextualized, and thus something other. On the other hand, since so mush has already been said and done in the field of photography, textual and semantic readings of photographic images, the sociopolitical or feminist analysis of the circulation and meaning of photography, the appropriation of photography in artistic practices, perhaps what is left in current photography is a metacritical reading of photography against photographic precedents, or to simply distance oneself from the readings and rely on the visual, the poetry. I would opt to view On Road photographs on its visual terms, as an intermediary between painting and photography. The black thick borders, the compositional device that reminds me of the inherent apparatus of framing in photography encourage me to define the prints in terms of photographic practices. On the other hand, the powerful visual impact of the sizeable images is something that is quite beyond documentation or everyday photography and I am inclined to gaze at the images as epic, poetic, emotional and beautiful.

카메라 렌즈에 포착된 대상을 편집하고 규정하는 틀, 하나의 장치라고 할 수 있는 사진의 프레임은 이정진의 사진 작업을 이해하는데 있어서 중요하다. 편집한 사진이나 우연히 찍은 스냅사진 모두 카메라 프레임에 의해 의미가 부여되고 이미지 기호로서 적용한다. 지난 10여년 동안 지속된 작업 과정에서 이정진은 카메라 프레임을 다양하게 적용하며, 그것을 독특하게 사진 이미지 생산에 개입시켜 작업하였다. 가장 최근 연작인사진을 논하는데 있어서도 작가가 대상을 프레임하는 방식이 주목되는 부분이다.

이정진은 1997년 연작을 마무리 하면서 작업을 발표하면서 카메라 프레임에 대한 제어와 통제를 포기하고자 했다고 기록한다. "작가 의식의 반영이라고 할 수 있는 사진구도 잡기를 포기함으로써 그 자가 의식 이전에 있는 대상자체의 '자연스러움'과 '있는 그대로'의 실체를 표현하고자 했다." 이정진은 사진가의 특권을 포기하면서 사진 작업의 한계를 극복하고자 했던 것이다. 이러한 의지의 결과는 현장의 생생함이 더 거칠게 표현된 마지막 사막 사진들이었다.

그 이후에 발표한 연작은 이전 작업과는 또 다른 풍경을 보여주는 것이었으며, 이정진은 이 작업을 통해 그의 가장 추상적이면서 회화적인 사진을 제작하였다. 바다를 소재로 선택한 것은 작가의 새로운 이미지의 구현이었다. 바다 수면의 잔잔한 물결, 바다와 모래가 만나는 해안선 등을 전면에 펼쳐 보이는 연작은 프레임의 장치가 담아낼 수 없는 광대한 바다를 소재로 그 풍경의 단편만을 보여주고 있다. 이것들은 추상 모노크롬 회화와도 흡사한 사진들이다. 한눈에 들어오는 바닷가 풍경이 아닌 바다 그 자체를 선택함으로써 작가는 매우 일반적인 물의 성질을 사진으로 담아내고 있고, 바다라는 풍경을 물이라는 하나의 물상으로 프레임하였다. 이정진의 연작은 도큐멘트로서 사진 기능을 부정하는 반면 사진의 대상은 추상 이미지로서, 초현실적인 대상으로서 제시되었다.

가장 최근 작업인 연작은 이정진의 이전 작업과는 현저히 다르면서도 유사한 접근 방식을 갖고 있다. 90년대 초에 제작한 연작과 비교해 볼 때, 역시 하나의 기행사진이다. 연작들이 광활하고 원초적인 자연 풍경 속의 단면들을 보여주고 있는 것에 반해, 연작은 주로 인간의 삶이 배어 있는 '한국 풍경'의 단면들을 보여주고 있다. 언젠가 지나가본 듯한 시골길 모퉁이, 농촌의 황량한 들판, 해안가 마을, 버려진 건물이나 창고의 외장, 버스 정류장 등 대부분 그의 풍경들은 평범한 일상의 모습이고, 그에 대한 기록은 지역성으로 인하여 한국적이라고도 할 수 있다. 그러나 작가가 보는 이 풍경들은 자가 내면의 은유와 결합해 시간과 공간을 넘어서 초현실성을 내포하고 있다. 버스 정류장에 걸린 시계는 우리에게 과거로의 여행을 떠나게 하고 텅 빈 해안의 작은 의자는 이정진 자화상의 또다른 은유이다. 늘 거기 있었던 시골 마을의 소나무는 오히려 합성된 사진처럼 부자연스럽다. 이 모든 상황들은 연출되지 않은 채 이정진의 카메라에 의해 각색된 새로운 이야깃거리를 제공하고 있다. 이 사진들은 내용 면에서는 시적이고, 보여주는 사진의 표현 형식 면에서는 오히려 스크린에 비춰진 영화의 한장면에 가깝다.

연작에서 새롭게 시도되고 있는 것은 사진의 형식이다. 모든사진들은 두터운 짙은 검정색 띠가 사진 테두리를 에워싸고 있고, 이는 개념적으로나 시각적으로 작품을 이해하는데 중요한 작용을 한다. 이 테두리는 사진을 하나의 회화적인 그림으로서 편집하고 이미지를 완성시킨다. 시각적으로 이 테두리는 영화 필름을 확대하여 영화 장면의 스틸을 보는 듯한 형식이다. 테두리는 하나의 화면을 구성하는 방식이면서 사진적인 기호이다. 현존하는 시간과 공간이 프레임에 의해 사진 화면에 고정되고 그 현장성은 프레임의 특수성에 의해 회화적인 도큐멘트가 아닌 회화적인 영역으로 전이된다. 그 프레임 안에 담겨진 장면에서는 시간적인, 공간적인 의미가 불투명해진다. 사진들은 빛 바랜 과거 시간을 재현하는 듯한 서정적인 이미지들이다. 개념적이기 보다는 시적이다. 작가가 사막과 바다 연작에서 편집의 기능을 부인하였던것과는 역으로 에서는 사진의 프레임 기능을 두드러지게 부각시키고 있다. 그래서 이들은 아름답게 편집된 그림들이고, 그의 여정속에서 담아온 개별적인 순간들의 재현이라는 것을 프레임을 통해 제시하고 있다.

이정진의 사진은 회화를 닮았다. 기술적으로 그의 사진은 기계적인 복제품이 아니고 작가가 직접 붓으로 리퀴드 라이트라는 감광유제를 한지에 발라 코팅을 하고, 그위에 인화하는 방식으로 작업한다. 그래서 프린트마다 그 화면에 담겨진 붓자국들은 서로 다를 수 밖에 없고 동일한 두 장의 프린트가 제작된다는 것은 원론적으로는 불가능하다. 한지의 습성에 의해 사진 이미지는 스며드는 듯, 화면에서 배어나오는 듯하며 세부적인 디테일이 생략되면서 명암의 대비도 현저히 부두러워진다. 이러한 제작 방식이나 한지 등 특수 종이의 사용과 회화적인 화면 연출은 특히 19세기 말 회화주의(Pictorialist) 사진 작가들에 의해 한때 성행하였다. 초기 사진 작가들도 그러했듯이 이정진도 사진의 위상을 예술적이고 회화적인 작품으로서 인식하고, 본인의 작업을 사진이라는 고정된 장르로 규정하는 것 자체에 대해 의문을 갖는다. 기존 사진의 기법을 이용하면서 사진의 독특한 이미지 기호를 언어로 구사하되 그의 작업은 회화적인 것이다. 결국 19세기 사진의 선례에 대한 메타 작업이기도 하면서, 풍경을 읽어내는 이정진의 시각과 그 표현 방법은 사진 예술에서의 '사진적'이라는 의미를 폭넓게 확장시켰다고 할 수 있다

Jungjin Lee writes about her last series of American Desert photographs in 1997 that she attempted to resign the photographer's control of the frame as she concluded her representations of rhe desert landscape, And thereby the artist intended the natural presence of the landscape to come across in her photographs and the object to present itself, without the interjection of the artist's control or intentionality. It was an attempt to conclude the desert series by giving up the photographer's privilege over the photographed object. Therefore she chose methods of placing herself as part of the photographed object, part of the landscape, and mot in front of the camera. The result was a more vivid and untamed representation of the desert,what I sense was in a way an homage to the vast desert land which she had visited for years.

In her following sequel titled the Ocean Series, the type of landscape and the visual effect of jungjin Lee's photography had changed to a great extent. The choice of ocean as a subject matter was obviously significant. In the images of different textures of water ripples, water and sand surfaces, Jungjin Lee has framed an indistinct detail, or portion, of a landscape that is too vast to be captured by any framing device. And therefore the result is also a photography that visually works as abstract painting. In the choice of ocean, rather than seaside landscape, in the renditions of the general properties of water (and sand), and the framing of ocean as water, Jungjin Lee's ocean pictures deny the documentary function of photography. It is the most abstract and painterly work of the artist. The photographed object appears abstract and surreal in front of the camera, and the framing has simply recognized and captured such inherent properties of the object. The artist's involvement in the Ocean series has been to frame the natural properties of the landscape and it is the function of framing in which photography and painting are most different, although the visual image produced might be similar in effect.

The most recent On Road series is starkly different from her earlier works but it also shares some affinities with Jungjin Lee' s previous output. It is in some ways a continuum of her American Desert series from the early 90s in that On Road is also the result of her travels. As in her representations of the desert landscape, Jungjin Lee does not opt for vast vistas or scenic nature, but her interest remains on chance encounters with odd pieces of visual detail, with ambiguous formations in natural or manmade environment.

Jungjin Lee has produced quite a wide range of different images from around the countryside in remote areas in Korea, and others from abroad-scenes of empty barren fields, or haunting building facades, an abandoned street corner in a deserted old village, a serene fishing village, beautiful still shots of trees and houses. Most of her landscapes are distinctly Korean, where the horizon line, architecture, and types of trees are specifically local. The object, the scene that captivated the artist has been freeze-framed. Everything is very still: there is no suggestion of life or movement, but a complete silence lulls over the scenes where time stands still.

The unique aspect of the On Road series is the special format of the photographs. All the photos are bordered by a jet black thick border which forms a conceptually and visually important element in viewing the photographs. The borders complete the image, edit the image as a pictorial unit. Visually it immediately reminds one of viewing a blown-up strip of film wherein all stills are framed by a continuous black border. The border is a compositional element as well as a semantic sign-it renders the photographic image into a freeze-frame film still, that is a cinematic moment. It thus becomes a frozen moment from time and place, but the temporal and spatial aspect of the On Road photographs is ambiguous. The time is non specific, of rather there is an antiquated look to the images, suggestive of a distant past. The On Road photos are therefore not documents of a journey, but an aesthetic moment. It is a scene of poetry rather than analysis, a "rarefied cameo." And in accord to such representations, the artist has chosen to reemphasize the framing device of her photographs. Whereas she renounced the editorial function of framing in her late American Desert or Ocean series, the framing is made manifest in On Road. These are beautifully composed pictures, and photographed and presented as autonomous monents from her journey, as complete painterly pictures.

In many ways Jungjin Lee's photography is close to painting. Technically her prints are not mechanically reproduced multiples. The artist brushes a coating of light sensitive emulsion on handmade rice paper which produces brush marks on the imprint. These irregular brush marks capture the photographic image, and thus the layer of brush marks is visible through the photograph.This produces a painterly quality which is further enhanced by the use of Hanji paper which absorbs crisp details and strong contrasts of lights and darks.

The natural off white color and mat absorbent surface texture of the printing paper produce a soft and blurred image. Not unlike the Pictorialist photographer's work from the late 19th century, Jungjin Lee's work is also suggestive of the intentions of the early practitioners of photography who opted for such technique and material to elevate the status of photograph as the aesthetic image on a par with painting. But in dong so, Jungjin Lee's prints appear completely unique within current practices among photographers.

It seems that the status of photography as art has become even more problematic than it was during its infancy in the latter half of the 19th century. If anything or everything in terms of the visual image around us in daily life is photographic, then what are the viable conditions that are applied to evaluate good photography, or photography with artistic merit? Besides, with the load of photography discourse in circulation the informed viewer may be burdened by readings about what Barthes defined as denotation and connotation in the photographic image so that what is photographed is not an innocent documentatiopn, rather it is actually a myth and therefore not really what it looks like, but represents something that is culturally, politically and historically contextualized, and thus something other. On the other hand, since so mush has already been said and done in the field of photography, textual and semantic readings of photographic images, the sociopolitical or feminist analysis of the circulation and meaning of photography, the appropriation of photography in artistic practices, perhaps what is left in current photography is a metacritical reading of photography against photographic precedents, or to simply distance oneself from the readings and rely on the visual, the poetry. I would opt to view On Road photographs on its visual terms, as an intermediary between painting and photography. The black thick borders, the compositional device that reminds me of the inherent apparatus of framing in photography encourage me to define the prints in terms of photographic practices. On the other hand, the powerful visual impact of the sizeable images is something that is quite beyond documentation or everyday photography and I am inclined to gaze at the images as epic, poetic, emotional and beautiful.

카메라 렌즈에 포착된 대상을 편집하고 규정하는 틀, 하나의 장치라고 할 수 있는 사진의 프레임은 이정진의 사진 작업을 이해하는데 있어서 중요하다. 편집한 사진이나 우연히 찍은 스냅사진 모두 카메라 프레임에 의해 의미가 부여되고 이미지 기호로서 적용한다. 지난 10여년 동안 지속된 작업 과정에서 이정진은 카메라 프레임을 다양하게 적용하며, 그것을 독특하게 사진 이미지 생산에 개입시켜 작업하였다. 가장 최근 연작인사진을 논하는데 있어서도 작가가 대상을 프레임하는 방식이 주목되는 부분이다.

이정진은 1997년 연작을 마무리 하면서 작업을 발표하면서 카메라 프레임에 대한 제어와 통제를 포기하고자 했다고 기록한다. "작가 의식의 반영이라고 할 수 있는 사진구도 잡기를 포기함으로써 그 자가 의식 이전에 있는 대상자체의 '자연스러움'과 '있는 그대로'의 실체를 표현하고자 했다." 이정진은 사진가의 특권을 포기하면서 사진 작업의 한계를 극복하고자 했던 것이다. 이러한 의지의 결과는 현장의 생생함이 더 거칠게 표현된 마지막 사막 사진들이었다.

그 이후에 발표한 연작은 이전 작업과는 또 다른 풍경을 보여주는 것이었으며, 이정진은 이 작업을 통해 그의 가장 추상적이면서 회화적인 사진을 제작하였다. 바다를 소재로 선택한 것은 작가의 새로운 이미지의 구현이었다. 바다 수면의 잔잔한 물결, 바다와 모래가 만나는 해안선 등을 전면에 펼쳐 보이는 연작은 프레임의 장치가 담아낼 수 없는 광대한 바다를 소재로 그 풍경의 단편만을 보여주고 있다. 이것들은 추상 모노크롬 회화와도 흡사한 사진들이다. 한눈에 들어오는 바닷가 풍경이 아닌 바다 그 자체를 선택함으로써 작가는 매우 일반적인 물의 성질을 사진으로 담아내고 있고, 바다라는 풍경을 물이라는 하나의 물상으로 프레임하였다. 이정진의 연작은 도큐멘트로서 사진 기능을 부정하는 반면 사진의 대상은 추상 이미지로서, 초현실적인 대상으로서 제시되었다.

가장 최근 작업인 연작은 이정진의 이전 작업과는 현저히 다르면서도 유사한 접근 방식을 갖고 있다. 90년대 초에 제작한 연작과 비교해 볼 때, 역시 하나의 기행사진이다. 연작들이 광활하고 원초적인 자연 풍경 속의 단면들을 보여주고 있는 것에 반해, 연작은 주로 인간의 삶이 배어 있는 '한국 풍경'의 단면들을 보여주고 있다. 언젠가 지나가본 듯한 시골길 모퉁이, 농촌의 황량한 들판, 해안가 마을, 버려진 건물이나 창고의 외장, 버스 정류장 등 대부분 그의 풍경들은 평범한 일상의 모습이고, 그에 대한 기록은 지역성으로 인하여 한국적이라고도 할 수 있다. 그러나 작가가 보는 이 풍경들은 자가 내면의 은유와 결합해 시간과 공간을 넘어서 초현실성을 내포하고 있다. 버스 정류장에 걸린 시계는 우리에게 과거로의 여행을 떠나게 하고 텅 빈 해안의 작은 의자는 이정진 자화상의 또다른 은유이다. 늘 거기 있었던 시골 마을의 소나무는 오히려 합성된 사진처럼 부자연스럽다. 이 모든 상황들은 연출되지 않은 채 이정진의 카메라에 의해 각색된 새로운 이야깃거리를 제공하고 있다. 이 사진들은 내용 면에서는 시적이고, 보여주는 사진의 표현 형식 면에서는 오히려 스크린에 비춰진 영화의 한장면에 가깝다.

연작에서 새롭게 시도되고 있는 것은 사진의 형식이다. 모든사진들은 두터운 짙은 검정색 띠가 사진 테두리를 에워싸고 있고, 이는 개념적으로나 시각적으로 작품을 이해하는데 중요한 작용을 한다. 이 테두리는 사진을 하나의 회화적인 그림으로서 편집하고 이미지를 완성시킨다. 시각적으로 이 테두리는 영화 필름을 확대하여 영화 장면의 스틸을 보는 듯한 형식이다. 테두리는 하나의 화면을 구성하는 방식이면서 사진적인 기호이다. 현존하는 시간과 공간이 프레임에 의해 사진 화면에 고정되고 그 현장성은 프레임의 특수성에 의해 회화적인 도큐멘트가 아닌 회화적인 영역으로 전이된다. 그 프레임 안에 담겨진 장면에서는 시간적인, 공간적인 의미가 불투명해진다. 사진들은 빛 바랜 과거 시간을 재현하는 듯한 서정적인 이미지들이다. 개념적이기 보다는 시적이다. 작가가 사막과 바다 연작에서 편집의 기능을 부인하였던것과는 역으로 에서는 사진의 프레임 기능을 두드러지게 부각시키고 있다. 그래서 이들은 아름답게 편집된 그림들이고, 그의 여정속에서 담아온 개별적인 순간들의 재현이라는 것을 프레임을 통해 제시하고 있다.

이정진의 사진은 회화를 닮았다. 기술적으로 그의 사진은 기계적인 복제품이 아니고 작가가 직접 붓으로 리퀴드 라이트라는 감광유제를 한지에 발라 코팅을 하고, 그위에 인화하는 방식으로 작업한다. 그래서 프린트마다 그 화면에 담겨진 붓자국들은 서로 다를 수 밖에 없고 동일한 두 장의 프린트가 제작된다는 것은 원론적으로는 불가능하다. 한지의 습성에 의해 사진 이미지는 스며드는 듯, 화면에서 배어나오는 듯하며 세부적인 디테일이 생략되면서 명암의 대비도 현저히 부두러워진다. 이러한 제작 방식이나 한지 등 특수 종이의 사용과 회화적인 화면 연출은 특히 19세기 말 회화주의(Pictorialist) 사진 작가들에 의해 한때 성행하였다. 초기 사진 작가들도 그러했듯이 이정진도 사진의 위상을 예술적이고 회화적인 작품으로서 인식하고, 본인의 작업을 사진이라는 고정된 장르로 규정하는 것 자체에 대해 의문을 갖는다. 기존 사진의 기법을 이용하면서 사진의 독특한 이미지 기호를 언어로 구사하되 그의 작업은 회화적인 것이다. 결국 19세기 사진의 선례에 대한 메타 작업이기도 하면서, 풍경을 읽어내는 이정진의 시각과 그 표현 방법은 사진 예술에서의 '사진적'이라는 의미를 폭넓게 확장시켰다고 할 수 있다

WORKS

|

On Road |

On Road |

|